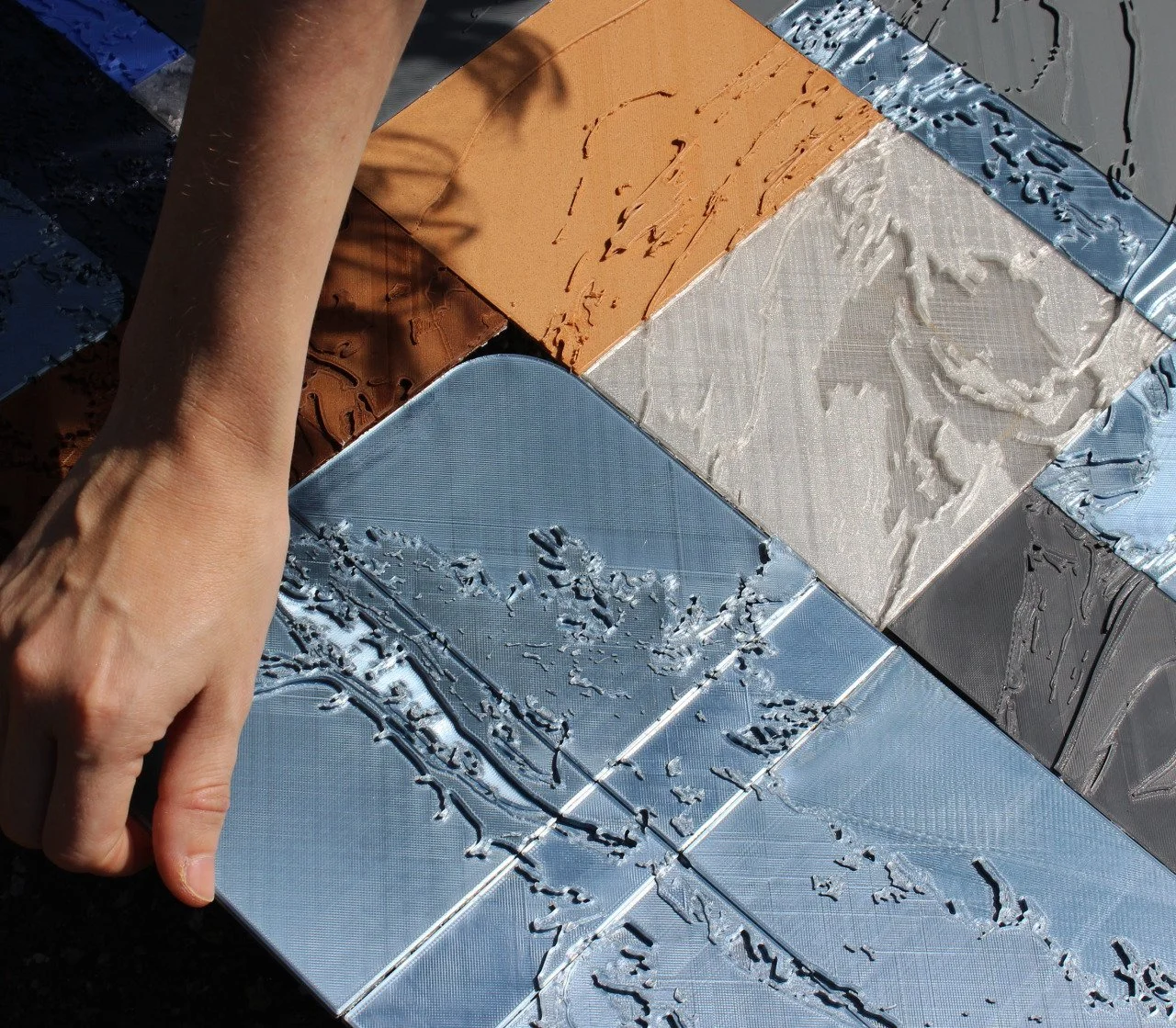

Benedetta Pompili on conversing with matter

Photo: Femke Reijerman

Benedetta Pompili is an Italian interdisciplinary designer currently based in Amsterdam. Her practice is focused on a dedication to earthwork ethics and local narratives, and she explores making processes, rethinking them for sustainability aims. We had a conversation with the designer about savior faire, toxicity and the dialogue between maker and material.

#Maren: Tell us a bit about yourself and what led you to this field of practice!

I studied design because I wanted to be able to choose, and I desired to instil care in the way ordinary things are thought and created. To do it, I needed to learn how things are made, so I found myself meeting craftspeople and diving into various materials and techniques. Along the process, I realised the need to play with the traditional thinking and making process. It is about looking back in search of a glimpse of unrealised possibilities. Maybe it’s because I’m from Italy, where, with a heavy heart, I have seen and heard of so much savoir faire (= know-how, red.anm) getting lost. I feel a propositive, maybe even utopian form of nostalgia, that sees progress in unseen bits of craft knowledge developed long ago, in a – not too much – different time.

#Maren: Per now you mainly work with ceramics - what attracted you to this material in particular?

Ceramics have been flourishing in my home region and town, Pesaro, since the 14th century. Even if coming from a modest family, I remember a few but good ceramics pieces always being present in the room. I remember my mother handling them with extreme care and literally yelling in pain if the other members of the family weren’t paying enough attention while washing or moving that mug or plate. Some pieces weren’t even allowed to be used. I guess this aura of preciousness and beauty grew in me great admiration for the medium. In the end, this led me to study design in Faenza, a small Italian city considered to be the best for ceramic making, rather than the more international and cooler Milano.

#Maren: It sounds like an inherited and emotional respect of both craft and material. What was it then that led you to the Netherlands, and to Design Academy Eindhoven? And what met you there?

I went to Design Academy for the same desire to learn crafts. At the time of the end of my BA, I was looking up to Martino Gamper, Max Lamb, Sigve Knutson, and Formafantasma. As a woman, I dreamt of learning by doing too. At DAE I finally had the chance to dive into the making, with the constant support of a growing critical sense. To design having in mind the world - its intricacies, entanglements and future possibilities.

#Maren: Which to me sounds like keywords that relate to your graduation project. What can you tell me about it?

“Conversing with Matter” starts on the potter’s wheel. The technique changed completely my perception of clay. You can feel the character of the material and converse with it, as long as you bend to the clay, listen to it, observe it. We perceive clay as ordinary and widely available. Nowadays, the clay distributed around the world comes from a few pure and ancient pits. Differently, in the past, ceramic productions followed the water bodies and moved along and with the resources. The river clay is still in continuous formation and everywhere unique, but of course is influenced by what gets dispersed into water. Clay works as a sponge for heavy metals or dioxins. So, “Conversing With Matter” suggests some possibilities to harvest the material locally and to extract as little as possible by reusing inorganic waste as a filler. It’s to reach this aim that I met asbestos. After the treatment it becomes harmless but stigmatised silica, that became a material I filled the clay with. In this way, on the one hand half of the material comes from the landfill, where it would stay toxic, threatening the life of the animals and the people working or living nearby, and preventing landfill mining. On the other hand, the clay acquires insulating properties and lightness. It’s an experiment that entangles different matters and stigma.

#Maren: How did you come to work with asbestos and toxity?

Asbestos came naturally as a part of my process for its properties and its inactive extractive status, rather than for its toxic nature. I didn’t and don’t want to work with toxic materials as much as possible. Nevertheless, I find the notion of toxicity extremely compelling to highlight the circularity of things, which is the way nature works. When discharged, toxic elements stay in the environment, they spread often invisibly, in ways that question human control. From my perspective, toxicity helps to understand that every material has always consequences we don’t see or we simply don’t want to look at.

#Maren: I am curious about what I perceive as an interest in the cultural aspects of the clay and craftsmanship, in combination with the more scientific and practical research into toxicity. Is this combination of storytelling and the poetic with looking for actual, practical solutions important to you? And where is the project going from here?

When I think about things, I don’t think of solutions, although I enjoy them to be true to their origins, embody them and somehow being active towards the context they’re in. Maybe it’s due to my industrial design background. However, I don’t perceive my project as concluded. The Techfellowship programme at Rijksakademie is allowing me to keep exploring technical aspects I didn’t have the knowledge or the time for before - it’s an ongoing process. Meanwhile I’m deepening my knowledge into clay, focusing on techniques and on how making the processes more sustainable.

#Maren: Lastly; the title of your project is “Conversing With Matter”. Can you tell me more about the idea behind that title?

When I say “conversing” with matter I mean that any material while being bent, crossed, woven, or even crunched has an active role. It’s a dialogue. The material resists and it’s reaction determines the way we structure our reality, culture, knowledge. We are matter adapting to other matters. The realization of this entanglement of forces, I believe, produces a unique and precious form of humbleness. The maker’s one.